Exploring the complexities of canine epilepsy

Imagine you’re at a giant sports stadium with millions of people. Now imagine every person yelling the word “goal!” at the exact same time. The possibility of that unified shouting would be overwhelming and a rare occurrence.

In a nutshell, this is how Dr. Fiona James would try to very simply describe a seizure to a pet owner: in this analogy the sports stadium is the brain, the millions of people in the crowd are the neurons (specialized cells in the brain) and the word they cheer together in unison is a seizure.

James explains her work as a veterinary specialist (to measure, record and analyze a seizure) with the same analogy – it involves placing very precise microphones located in the ceilings throughout the stadium (the brain) to try to pick up the words being spoken by the crowd (seizure) to better decipher what’s being said by the people (neurons).

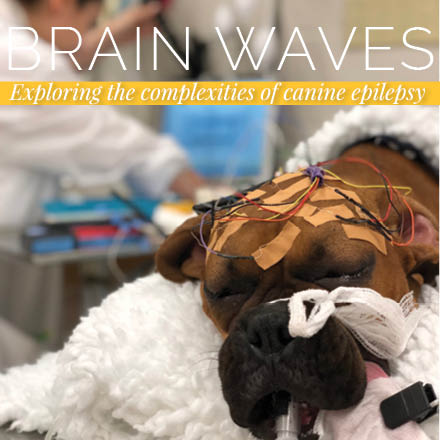

IN PHOTO (left): OVC Neurology patient, Izzy, receives an EEG.

The “microphones” she uses are a component of a monitoring method to record electrical activity in the brain called electroencephalography (EEG). Conducting an EEG involves placing tiny, non-invasive electrodes on the head. By interpreting the brain waves of data transmitted by the microphones (electrodes), neurologists can diagnose and decode what type of seizure a patient may be experiencing. In the comparison, a generalized (grand mal) seizure would be every single person in the crowd saying the same word. A focal (petit mal) seizure would be half the stadium saying the same word. The analogy isn’t perfect; in reality it is much more complex, but the story helps many pet owners understand the mechanics of a seizure.

“The brain is intricate. Many of the same networks in the brain responsible for learning and forming memories are also associated with epilepsy,” James says. In the analogy, the neurons in some specific regions of the brain, for example, the hippocampus and the amygdala, are the rowdy individuals in the stadium who start the commotion (seizure).

According to Epilepsy Canada it is estimated that 0.6% of Canadians have epilepsy, with approximately 15,500 new human cases diagnosed each year. In veterinary medicine, working dog breeds such as retrievers, shepherds, collies and hounds are more commonly diagnosed with the condition. James says that humans and dogs with epilepsy share many parallels, such as similar types of seizures, similar drugs for treatment and the disorder is naturally-occurring in both species.

James is a board-certified veterinary neurologist at the Ontario Veterinary College (OVC), University of Guelph and a leading global expert in canine epilepsy. In 2017, she was part of an international team that discovered a defect in a gene in Rhodesian Ridgeback dogs that had never been associated with epilepsy in humans

or animals before. The breakthrough, funded in part by OVC Pet Trust,

will help researchers explore new treatments and open new pathways for future investigations of epilepsy in dogs. It may hold promise for humans with the neurological disorder as

well.

The findings from this study are significant; and while the discovery doesn’t pinpoint the cause of epilepsy, it brings us closer to understanding the disorder, as a whole. For James and her team, epilepsy is the most common medical referral to the Neurology Service at the OVC Companion Animal Hospital. She sees the most challenging, complex cases where the goals are usually to accurately diagnose, manage and adjust treatment.

James’ specialty is diagnosing seizures and epilepsy in dogs using awake EEG, a gold standard in human medicine. EEGs in veterinary medicine are performed by neurologists and have historically been conducted when the pet is under sedation or general anesthesia. But since clinicians can better detect seizures when patients are awake and moving around normally, James adapted a belt pack unit used in human medicine into a backpack for her canine patients, a first in the veterinary world. The backpack holds a wireless transmitter which records brain activity while the dog is awake and sends data back to a computer for analysis.

She is one of only a handful of people worldwide who are experts in placing EEG electrodes and interpreting awake EEG recordings in dogs, and she has worked extensively with collaborators and mentors at Toronto’s Hospital for Sick Children (SickKids) in her quest to better understand canine epilepsy.

James is currently gathering and analyzing data captured by EEGs in dogs around the world. Her goal is to make EEG tests easier, better and faster. Working with a number of global specialists, she hopes the data will help establish patterns and eventually lead to guiding treatment decisions in pets.

“We know that, unfortunately, 30 per cent of dogs with epilepsy do not respond to their medications. In veterinary medicine, we currently do not have recommendations based on scientific evidence for why one treatment may work better than another,” James says.

James is also involved in collaborative work at OVC studying how stem cells develop in the brains of epileptic patients and the role big data may play when comparing EEG seizure data in dogs versus humans.

“Many dogs with epilepsy can manage their disorder with treatment from their primary care veterinarian and have a very good quality of life. The better we can get at EEG, the more we can understand about the disorder and help the patients who have difficulty controlling their seizures have more good days than bad ones with their families,” James says.

What is Epilepsy?

Epilepsy is defined as a disorder of the brain characterized by an enduring predisposition to generate epileptic seizure. This definition is usually practically applied to a patient who has had at least two unprovoked epileptic seizures less than 24 hours apart. The term “seizure” is used for any sudden, short-lasting and transient event, but it does not necessarily imply that the event is epileptic.

What to do if your dog has a seizure.

A seizure is a major metabolic event and has a significant impact on the brain and body as a whole. If you suspect your pet has had or is having a seizure:

- Keep your pet cool. Seizures can raise a dog’s core body temperature. Provide water and air conditioning if possible. Spray cold water on their feet and put ice packs in their arm pits.

- Never put your hands in or around the mouth of a pet who is having a seizure. They may bite their tongue, but they will not swallow it. Since dogs are usually unconscious and not aware of what’s happening during a seizure, they may bite or cause injury to people.

- If you need to move your pet to a safe place or out of the direct sun while they are having a seizure, roll them onto a blanket and drag them on it to move them.

- Many dogs will be confused and disoriented after a seizure. Keep a close eye on them to make sure they’re safe until you can contact your veterinarian to discuss next steps.

Dr. Fiona James is a member of the International Veterinary Epilepsy Taskforce (IVETF) and an OVC Pet Trust-funded researcher.

Read more in the fall / winter issue of Best Friends Magazine.