First-of-its-kind research reveals impact of burnout and compassion fatigue on provision of care

Pet ownership in Canada is at an all-time high, thanks to so-called “pandemic puppies”, “covid kittens” and other animals finding their forever homes. Now, as families incorporate new companion animals into their households, many are encountering an unexpected challenge – there’s higher demand and longer wait times for veterinary care.

Dr. Andria Jones-Bitton, director of well-being programming for the Ontario Veterinary College (OVC) and OVC researcher with a focus on the epidemiology of mental health in veterinarians, veterinary students and agricultural producers, says many veterinarians are seeing high demand for their services at a time when clinics are also adjusting to new and changing public health protections.

Dr. Andria Jones-Bitton, director of well-being programming for the Ontario Veterinary College (OVC) and OVC researcher with a focus on the epidemiology of mental health in veterinarians, veterinary students and agricultural producers, says many veterinarians are seeing high demand for their services at a time when clinics are also adjusting to new and changing public health protections.

“Veterinary hospitals have seen more pets, and a decrease in the number of people that can be present in clinics who’ve transitioned to offer curb-side medicine for their patients. That, in combination with other factors, has put a real demand on veterinarians that we haven’t seen before,” says Jones-Bitton. “Increased veterinary demand has been compounded by other stressors resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic: veterinarian and staff shortages, illness resulting from COVID, lack of child care, clients taking frustrations out on staff, and burnout.”

Jones-Bitton and then PhD candidate, Dr. Jennifer Perret, conducted research, believed to be the first of its kind, that examined the relationship between the mental health of veterinarians and the resulting client satisfaction. What her research team found was that the relationship was incredibly complex.

“We found that higher client satisfaction was associated with poor veterinarian mental health states, and lower client satisfaction was associated with mental health states more indicative of wellness. We suspect the higher levels of anxiety, emotional exhaustion and depersonalization amongst veterinarians with high client satisfaction may be explained by emotional labour – the effort expended to manage one's feelings while fulfilling the requirements and societal expectations of the job,” Jones-Bitton says. “Similarly, among human physicians, empathy has a well-documented association with patient satisfaction and is also hypothesized to increase the risk of burnout and empathic distress (also known as compassion fatigue).”

“We found that higher client satisfaction was associated with poor veterinarian mental health states, and lower client satisfaction was associated with mental health states more indicative of wellness. We suspect the higher levels of anxiety, emotional exhaustion and depersonalization amongst veterinarians with high client satisfaction may be explained by emotional labour – the effort expended to manage one's feelings while fulfilling the requirements and societal expectations of the job,” Jones-Bitton says. “Similarly, among human physicians, empathy has a well-documented association with patient satisfaction and is also hypothesized to increase the risk of burnout and empathic distress (also known as compassion fatigue).”

Jones-Bitton’s research raises the question: how can pet owners best support their veterinarian? What does it mean to be a good client?

Know your hospital’s protocols

To limit the spread of COVID-19 among clinic staff and the broader community, hospitals have adopted additional cleaning protocols, capacity restrictions and PPE policies into their existing operating procedures. It’s all part of continuing to provide the best, safest care possible, but at a slower pace.

“Everyone is doing their best, but some days it seems like there are ever-changing protocols, and that can feel overwhelming,” says Jones-Bitton. She notes paying attention to timelines and respectfully adhering to clinic requests goes a long way in ensuring appointments run smoothly for everyone.

Commit to your pet

Most families want only the best for their pet, always – and so does your veterinarian. Sometimes, though, a pet’s medical needs or behaviours change, and lead to difficult situations to navigate.

Most families want only the best for their pet, always – and so does your veterinarian. Sometimes, though, a pet’s medical needs or behaviours change, and lead to difficult situations to navigate.

“Unfortunately, sometimes veterinarians encounter situations we call ‘moral distress’ because they are asked to do something that is against their morals or what they believe is right,” says Jones-Bitton. “Of course, the overwhelming majority of clients understand that having a companion animal is a lifelong commitment. Nevertheless, veterinarians experience moral distress when they know there is something that they can do to help an animal, but there are barriers in the way for doing so: for example, a client’s inability or unwillingness to pay, as well as different value systems,” Jones-Bitton adds.

Beware of Dr. Google

While it’s natural for pet owners to turn to internet searches when we have concerns about our pet’s health, not all websites are credible, and most clients agree that it doesn’t replace a veterinarian’s expertise.

While it’s natural for pet owners to turn to internet searches when we have concerns about our pet’s health, not all websites are credible, and most clients agree that it doesn’t replace a veterinarian’s expertise.

Recent OVC research led by Dr. Deep Khosa with PhD candidate Nanette Lai explored how online searches may impact a client’s relationship with their veterinarian and revealed that in many cases clients have already consulted online resources before making an appointment at their veterinarian – in most cases, to help them decide if a visit was in fact warranted. The study also showed that pet owners expressed a preference to get information directly from their veterinarian.

“If you aren’t sure what online resources may or may not be credible sources of information, the best option is to ask your veterinarian directly. If possible, also ask them to make recommendations for reliable information sources that they would want you to read,” advises Khosa.

Be real about costs

For many clients, the most stressful aspect of veterinary care is the bill. And especially if a client doesn’t have pet insurance, everything comes at a cost.

“It’s hard for many people to put a veterinary bill into perspective, because in Canada we aren’t used to paying for our own healthcare or seeing an itemized bill,” says Jones-Bitton. “Keeping a veterinary clinic running comes at a high cost. The equipment, skilled teams and the facilities are essential to giving the very best care possible.”

“It’s hard for many people to put a veterinary bill into perspective, because in Canada we aren’t used to paying for our own healthcare or seeing an itemized bill,” says Jones-Bitton. “Keeping a veterinary clinic running comes at a high cost. The equipment, skilled teams and the facilities are essential to giving the very best care possible.”

Pet insurance, when it’s a viable option, can help ensure the best care is delivered to patients without cost being as big of a barrier, Jones-Bitton adds.

Communication is key

Between pandemic challenges and higher workloads everyone is experiencing, sometimes corralling pets through traffic to the clinic can feel more stressful than usual, Jones-Bitton says. Particularly if a client has a concern relating to their pet’s appointment or care, they are entitled to their feelings. But regardless of what kind of day they’ve had, it essential that communication between members of the veterinary team and clients is respectful.

“Strong relationships are built on trust, and respectfully communicating concerns is essential to strengthening your relationship with your veterinarian,” says Jones-Bitton. “At the end of the day, we are all human, and we all want the best possible outcomes for our animals.”

Research to the Rescue: How Evidence-Based Tools are Helping to Address the Problem

Veterinary medicine is an incredibly rewarding occupation. But by nature of the job, there are some stressors that are inherent to the veterinary profession that can have a negative impact on a veterinarian’s mental health. A growing body of research is looking at factors such as resilience, perceived stress, anxiety, depression, burnout and empathic distress (compassion fatigue) among veterinarians.

“Veterinarians see a lot of sickness, and sometimes despite best efforts, veterinarians don’t always see the outcomes they want,” says Jones-Bitton. “At times, when veterinarians connect with clients on grief and distress, it can be harmful to a veterinarian’s own emotional state and mental health. It is important to recognize that and manage veterinary mental health accordingly.”

Jones-Bitton works with colleagues to understand the risk factors associated with poor veterinarian mental health. She has also been instrumental in providing the field with evidence-based tools to address the problem.

Jones-Bitton works with colleagues to understand the risk factors associated with poor veterinarian mental health. She has also been instrumental in providing the field with evidence-based tools to address the problem.

Jones-Bitton has a new study underway with co-investigator Dr. Caroline Ritter at the Atlantic Veterinary College, and PhD students Tipsarp Kittisiam and Emily Morabito. “We have a new study to investigate early career veterinarians’ mental health from time of graduation through their first two years of practice. The results will help us develop training and resources to support veterinarians through this crucial transition period.”

The researcher has also led the development of a new curriculum to enhance resilience and wellbeing for student veterinarians at OVC. She notes that instructors are also teaching students about compassion, and how they can demonstrate compassion for others.

“It’s important that current veterinarians – and our students – appreciate that veterinary medicine is an incredibly rewarding profession, but it’s also burdened with stresses and challenges. Many positive psychology tools and well-being strategies can help,” says Jones-Bitton. “With that awareness, we can set them up for success in serving their patients and clients.”

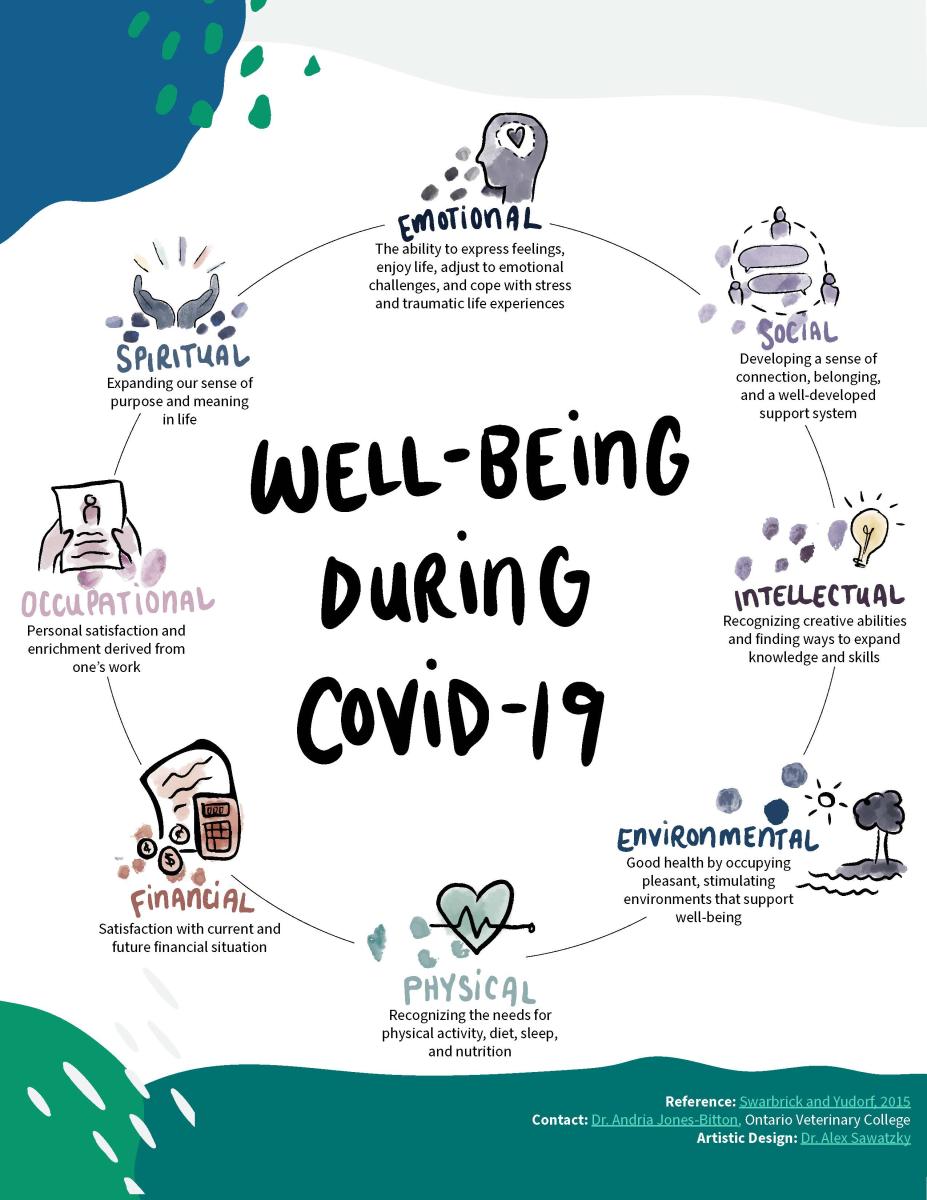

FREE Downloadable: Well-Being During COVID-19 Booklet.

Check out Dr. Andria Jones-Bitton’s Research Resources, including the Well-Being During COVID-19 Booklet, available in English, French and Spanish.

* This story originally appeared in the spring / summer 2022 issue of OVC Pet Trust's Best Friends Magazine. Join our community and subscribe to the pet magazine of the Ontario Veterinary College.