Dr. Fiona James studies comparative epilepsy, the field of veterinary neurology focused on the similarities and differences between humans and animals who experience the disease. She works extensively with mentors and collaborators at Toronto’s Hospital for Sick Children (SickKids) in her quest to better understand canine epilepsy. Photo credit: Spencer McMillan.

Clinician and scientist Dr. Fiona James sits at her computer, poring over an electroencephalogram—a type of test that measures brain activity—of one of her canine patients. Rows of brightly coloured squiggly lines on the image, paired with a video recording of the dog’s activities, reveal a particular type of activity in the brain accompanying the frequent facial twitches, suggesting that these are caused by seizures. This diagnostic test is one of many James will review this week, each one unveiling critical insight into how a seizure—an unexpected, jarring episode for some patients, or an unfortunately routine occurrence for others —affects her patients. One day, James hopes to be able to pinpoint the precise location that a seizure occurs in the brain of her four-legged patients—and maybe even cure their epilepsy altogether. That’s the goal.

In her role as a professor and a board-certified neurologist at the Ontario Veterinary College (OVC), James directly contributes to the improvement of pet health, not only for her clients, but around the world. Specifically, through her research, she aspires to find innovative and more effective ways to diagnose and treat canine epilepsy.

James is a global leader in the field of veterinary neurology and is a highly sought-after mentor for trainees who travel great distances to complete a neurology residency under her leadership. She is the go-to person for her veterinarian colleagues to call on for a neurology referral, and she provides guidance to fellow specialists as well. Perhaps most notably, she is one of only a handful of experts worldwide in interpreting awake EEG (or electroencephalography) brain recordings in dogs—a method for picturing functional states of the brain and measuring electrical activity. This method sets the gold standard for the diagnosis of seizures and epilepsy in people and dogs.

Today, OVC Pet Trust shadows James and her team in the clinic on the Neurology Service within the OVC Health Sciences Centre.

DAY ONE

0730

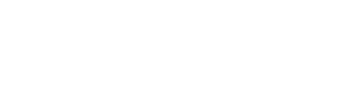

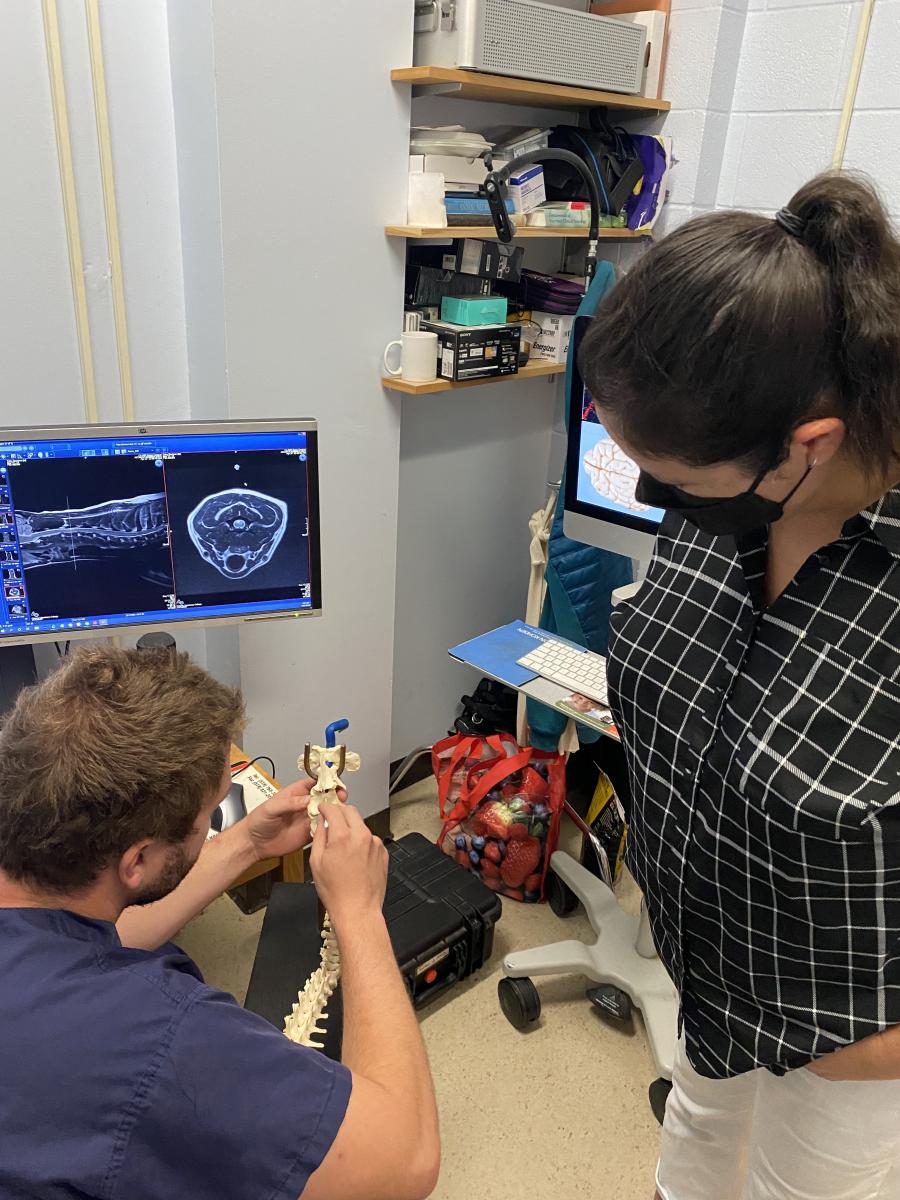

Case review of the day’s appointments is underway between neurology residents (trainees working to become board-certified neurologists) Drs. Gibrann Castillo Escotto and Stephen Everest. This morning will include three new patient appointments. The team diligently prepares their surgical plan for an upcoming procedure for a dog named Toby, plotting their path on the medical imaging. James guides the team with case management and maps out the tentative schedule for their day on the clinic floor.

Case review of the day’s appointments is underway between neurology residents (trainees working to become board-certified neurologists) Drs. Gibrann Castillo Escotto and Stephen Everest. This morning will include three new patient appointments. The team diligently prepares their surgical plan for an upcoming procedure for a dog named Toby, plotting their path on the medical imaging. James guides the team with case management and maps out the tentative schedule for their day on the clinic floor.

To be a good neurologist, you must have a good understanding of magnetic resonance imaging, or MRI—a medical imaging technique that creates detailed pictures of organs and tissues in the body. Neurologists constantly read and interpret MRIs. They tell a story—important details that are vital to understand what’s going on with their patient and how they may be able to help them.

0900

Castillo’s first appointment of the day is a Shar Pei who has been referred to OVC by their family veterinarian because of changes in behaviour that are suspected to be neurological in nature. Castillo begins to build a list of suspected causes for his patient’s condition. In medicine, generating a differential diagnosis list (DDx) is a method of clinical reasoning when physicians analyze a patient’s history, clinical signs or symptoms, physical examination and imaging results to prioritize the most likely diagnosis or cause of illness or disease.

Everest’s first appointment is a 13-year-old Wheaten Terrier named Bentley. After taking a complete history with Bentley’s family, Everest brings Bentley to the treatment room and examines him, performing a complete neurological (or “neuro,” in hospital lingo) exam. Bentley has been previously diagnosed with a tumour in his brainstem, the connection between the brain and the spinal cord. Everest and James examine Bentley’s prior MRI images and confirm that radiation therapy is the best treatment option for Bentley’s cancer, which his owner wants to pursue.

Everest’s first appointment is a 13-year-old Wheaten Terrier named Bentley. After taking a complete history with Bentley’s family, Everest brings Bentley to the treatment room and examines him, performing a complete neurological (or “neuro,” in hospital lingo) exam. Bentley has been previously diagnosed with a tumour in his brainstem, the connection between the brain and the spinal cord. Everest and James examine Bentley’s prior MRI images and confirm that radiation therapy is the best treatment option for Bentley’s cancer, which his owner wants to pursue.

While Everest reviews options with Bentley’s human, Castillo arrives with a two-year-old Husky named Tahoe. Castillo verbally presents Tahoe’s history and exam results to James, who picks up a marker and jots down possible differentials on the treatment room whiteboard to narrow down how the team can help Tahoe. She asks the team: “What are our next steps? What diagnostic imaging do we need to consider to learn more?”

While Everest reviews options with Bentley’s human, Castillo arrives with a two-year-old Husky named Tahoe. Castillo verbally presents Tahoe’s history and exam results to James, who picks up a marker and jots down possible differentials on the treatment room whiteboard to narrow down how the team can help Tahoe. She asks the team: “What are our next steps? What diagnostic imaging do we need to consider to learn more?”

The problem solving continues, and each patient is a puzzle for the team; the more information they have, the better job they can do at placing the puzzle’s pieces into the correct arrangement to form a complete picture.

0930

The day is in full swing as James reviews the MRI of a three-year-old Bulldog with a brain mass and consults with a rotating intern, Dr. Erica Fox, about the case. Discussion is centered around the history of the patient and clinical signs the dog is presenting with, including vision loss. The OVC HSC is a teaching hospital, and James asks Fox which tests she would recommend pursuing to assist in their investigation, which will involve internal consults with ophthalmology and oncology. At the same time, a new dog patient arrives in the treatment room, and a Doctor of Veterinary Medicine (DVM) student—one of five students on their neurology clinical rotation this week—presents the patient’s history to the neuro team. DVM students help monitor neurology patients who are at the OVC Companion Animal Hospital throughout the day, propose diagnostic tests and treatments, update clients about their pet’s progress and write medical records entries—all activities that provide them with clinical experiential learning opportunities in their fourth and final year of veterinary school.

1000

If the body was an organic computer, James compares the neuro system as the wiring—a system of elaborate and connective networks.

If the body was an organic computer, James compares the neuro system as the wiring—a system of elaborate and connective networks.

Neurolocalization is an essential tool for neurologists. In simple terms, it means being able to localize—or pinpoint— the area of the nervous system responsible for disease or disruption. The nervous system is a complex network of neurons (specialized cells) that enable parts of the body to communicate with one another; the body’s central nervous system (CNS) includes the brain and the spinal cord. The pathways of the nervous system are not continuous, but they’re intricately integrated, like millions of baton runners during a team relay race—sometimes it’s a single pass or multiple ones to complete the race (or circuit, in the case of neurons in the body), James explains. In the body-as-a-computer analogy, the spinal cord is the internet, relaying messages and information throughout the body. A neuro exam attempts to answer one pressing question: where have the wires been cut?

James shares that she had been training as a biophysicist specializing in neuroscience because of her fascination with the computational structure of the brain when she discovered the joy of working with animals, which led her to pursue her career in veterinary medicine.

1130

Castillo assesses a dog patient named Bear, an internal consult from the medicine service. If an animal is on pain medication, clinical signs can be masked during a neuro exam, he explains. Everest is on call this week, which means that in addition to his 10-to-12-hour days as a resident, he may be paged any time between the hours of approximately 6 p.m. until 8 a.m. for a neurology emergency. This may include a patient that’s having uncontrollable seizures or MUE. MUE stands for meningoencephalomyelitis of unknown etiology; it is an umbrella term describing inflammatory changes in the central nervous system with no suspected infectious cause in dogs, cats and even humans. MUE refers to inflammation of the brain and the surrounding fluid and tissues and is sometimes caused by an underlying autoimmune condition.

Castillo assesses a dog patient named Bear, an internal consult from the medicine service. If an animal is on pain medication, clinical signs can be masked during a neuro exam, he explains. Everest is on call this week, which means that in addition to his 10-to-12-hour days as a resident, he may be paged any time between the hours of approximately 6 p.m. until 8 a.m. for a neurology emergency. This may include a patient that’s having uncontrollable seizures or MUE. MUE stands for meningoencephalomyelitis of unknown etiology; it is an umbrella term describing inflammatory changes in the central nervous system with no suspected infectious cause in dogs, cats and even humans. MUE refers to inflammation of the brain and the surrounding fluid and tissues and is sometimes caused by an underlying autoimmune condition.

1300

James checks in on a student in her lab, Grace, who is working on an OVC Pet Trust-funded project examining the anatomy of brains of dogs who have epilepsy. Her project involves investigating the differences in connectivity — the wires and the pathways—on MRI to answer a simple question: if pathways are disrupted, does it affect whether a dog responds to treatment or not? Other projects within James’ lab examine the cases of dogs who do not respond to anti-seizure drugs with a goal to answer questions, like: Can we target a better treatment? Is there a way to identify severity of the disease, or a crystal ball to predict disease outcomes to help pet owners make decisions and find peace of mind?

James says that veterinary medicine is not good at localizing the origin of a seizure yet. “The ultimate goal of my research is to be able to very accurately pinpoint the location of seizures so we can consider surgery,” James says.

James says that veterinary medicine is not good at localizing the origin of a seizure yet. “The ultimate goal of my research is to be able to very accurately pinpoint the location of seizures so we can consider surgery,” James says.

What is the value of knowing where a seizure occurs in the brain?

James explains that in humans, seizures (and specifically where seizures start) can, in some cases, be precisely located in the brain, and surgery may sometimes be an option to remove or disconnect that part of the brain in an effort to reduce seizures. We don’t do this much in dogs yet, but it’s a technique that, in people, can be curative. Human epilepsy also has more specific sub-types of the disease, such as frontal lobe epilepsy or temporal lobe epilepsy. In dogs, there is just epilepsy (generalized or focal).

So, what does this all mean?

“Better diagnosis leads to a better treatment plan,” James states. “In the grand scheme of things, what we know is proven to help humans may help dogs. What we know about dogs may help humans too. If we can bring dog epilepsy to the human level of diagnosis and treatment, our two-way exchange between species will be strengthened,” she adds, pointing to her research collaboration with The Hospital for Sick Children (SickKids) as a key part of her mission to better understand canine epilepsy.

1400

The afternoon is underway with a follow-up appointment for a Golden Retriever named Lucy. OVC intern Dr. Makayla Farrell presents a new case to the neuro team. Most of the afternoon is filled with paperwork and evaluation of incoming referral requests from family veterinarians whose patients require the help of a neurology specialist.

1730

Rounds are complete for today, and James finishes them off with an impromptu pop quiz, pulling up radiographs, or X-rays, of a patient with a brain infection. “These are the details you’ll need to know for board certification,” she says to her residents. Rounds, an essential component of medical education, is a collaborative process when the team gathers and shares information about each patient’s condition, status and care plan. The discussion—and the teaching—is non-stop. The rest of the evening will include paperwork, medical record writing and prescription refills for patients.

DAY TWO

750

Everest examines Ruger in the hospital’s Intensive Care Unit (ICU), a dog who was admitted to the unit overnight while Everest was on-call. Ruger’s owners noticed his behaviour was unusual, and last night, he was suddenly unable to walk and became completely paralyzed in all four of his limbs.

Everest examines Ruger in the hospital’s Intensive Care Unit (ICU), a dog who was admitted to the unit overnight while Everest was on-call. Ruger’s owners noticed his behaviour was unusual, and last night, he was suddenly unable to walk and became completely paralyzed in all four of his limbs.

Days like today are an example of how the team delicately balances emergency patients and scheduled appointments and procedures. Today is Toby’s surgery; Ruger will have an MRI; and another patient named Oscar will have a spinal tap to rule out the presence of cancer cells or inflammation in his cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). CSF is the clear liquid that flows around the brain and the spinal cord in all animals and humans, acting as a cushion to protect the organs from injury or sudden impact. The purpose of a spinal tap is to analyze a patient’s CSF to help make a diagnosis; it can detect conditions like infection, cancer, tumours and other disorders.

1000

Patients are managed as a triage Registered Veterinary Technician (RVT) asks about another potential emergency arrival of a dog with back pain to the ICU. Castillo performs a neuro exam on Lainey, a cat, who is here for a recheck after being hospitalized the prior week with suspected cuterebriasis, a parasitic disease. Jackson, a dog, is here for an EEG to diagnose suspected focal seizures. Gunther, a long-haired Dachshund dog that was previously diagnosed with an MUE, is here today to receive a drug protocol to treat inflammation in his brain. The team also sees a dog patient with possible scoliosis, a rare type of spinal cord disease characterized by a curve of the spine.

Patients are managed as a triage Registered Veterinary Technician (RVT) asks about another potential emergency arrival of a dog with back pain to the ICU. Castillo performs a neuro exam on Lainey, a cat, who is here for a recheck after being hospitalized the prior week with suspected cuterebriasis, a parasitic disease. Jackson, a dog, is here for an EEG to diagnose suspected focal seizures. Gunther, a long-haired Dachshund dog that was previously diagnosed with an MUE, is here today to receive a drug protocol to treat inflammation in his brain. The team also sees a dog patient with possible scoliosis, a rare type of spinal cord disease characterized by a curve of the spine.

1107

Toby is prepared for surgery, anesthetized and wheeled into an operating room (OR) as RVT Jayme prepares Oscar’s spinal tap materials for Castillo.

1142

Everest and James scrub into Toby’s neurosurgery. While some neurosurgeries can be upwards of six hours in duration, the team is hopeful that Toby’s will take approximately three hours from start to close.

1245

Surgery is well underway, and Castillo has joined Everest and James in the OR. An intern comes in to consult with Castillo about a dog that has been admitted to the ICU who is experiencing uncontrollable cluster seizures —multiple seizures within a short period of time—sometimes life-threatening. Castillo scrubs out to consult on his patients in the ICU.

Surgery is well underway, and Castillo has joined Everest and James in the OR. An intern comes in to consult with Castillo about a dog that has been admitted to the ICU who is experiencing uncontrollable cluster seizures —multiple seizures within a short period of time—sometimes life-threatening. Castillo scrubs out to consult on his patients in the ICU.

1520

Toby is in recovery and as Everest and James return to the treatment room, Castillo presents two new hospitalized cases to them. One of those cases is Abby, a Cocker Spaniel dog, a patient who has been admitted to ICU with suspected bacterial meningoencephalitis, inflammation of the brain and spinal cord caused by an infection, which the team suspects may be causing focal seizures and other life-threatening clinical signs.

Toby is in recovery and as Everest and James return to the treatment room, Castillo presents two new hospitalized cases to them. One of those cases is Abby, a Cocker Spaniel dog, a patient who has been admitted to ICU with suspected bacterial meningoencephalitis, inflammation of the brain and spinal cord caused by an infection, which the team suspects may be causing focal seizures and other life-threatening clinical signs.

1700

Rounds today involve discussion about the patients in neurology’s care —both inpatients — animals that are currently hospitalized—and outpatients too: Toby, Lainey, Oscar, Jackson, Ruger, Abby and two other dogs. Everest prepares for an after-hours neurosurgery for an incoming emergency patient.

Throughout the whirlwind of exams and consultations, procedures and follow-ups, James remains a steady and calming presence in what can sometimes feel like the frenzy of it all. She is a passionate and accomplished teacher—mentoring, guiding and pushing her trainees and students to prepare them for a future in the specialty of neurology and general practice while providing thoughtful and compassionate care to their patients.

“It is incredibly satisfying to have the opportunity to try to solve a clinical problem after identifying it—whether it is for patients and their families, or on a grander scale designing studies to probe the bigger issues,” James says. “On top of that, the delight of seeing a trainee put it together for the first time and have that ‘ah-hah!’ moment is so rewarding,” she smiles, adding that she is reminded daily how much we still have to learn about the nervous system – it’s all part of the beauty and intrigue of constant progress and innovation in pursuit of discovery as a scientist.

“It is incredibly satisfying to have the opportunity to try to solve a clinical problem after identifying it—whether it is for patients and their families, or on a grander scale designing studies to probe the bigger issues,” James says. “On top of that, the delight of seeing a trainee put it together for the first time and have that ‘ah-hah!’ moment is so rewarding,” she smiles, adding that she is reminded daily how much we still have to learn about the nervous system – it’s all part of the beauty and intrigue of constant progress and innovation in pursuit of discovery as a scientist.

“Neurological problems can be scary and intimidating because we can’t see the cause, not like when you have a broken leg. Similarly, that first seizure you ever see seems to take forever to stop. But not all the causes and diseases are bad; many can be managed with a decent quality of life. Neurologists often find themselves recommending ‘time’—to give our pet friends a chance to heal,” James says.

Story photography by Spencer McMillan and Ashleigh Martyn.

This story originally appeared in the fall 2022 / winter 2023 issue of OVC Pet Trust's Best Friends Magazine. Join our community and subscribe to the pet magazine of the Ontario Veterinary College.