How fecal transplants have the potential to treat disease in dogs

Medical science has entered the era of the microbiome. The microbiome is a part of all living species and it is made up of microbes, bacteria, viruses, fungi and other microorganisms that live inside the body and help keep us healthy. The importance of gut health – how we ingest, digest and expel the food we put in our systems – is not just relevant in human medicine; veterinary specialists worldwide are also tackling the subject, including researchers at the University of Guelph’s Ontario Veterinary College (OVC).

Dr. Shauna Blois, a board-certified internal medicine specialist, says we still have a lot to learn about how the microbiome interacts with states of health and disease in the body. Interest in the scientific community is developing at a rapid rate to determine links between disease and the body’s microbiome.

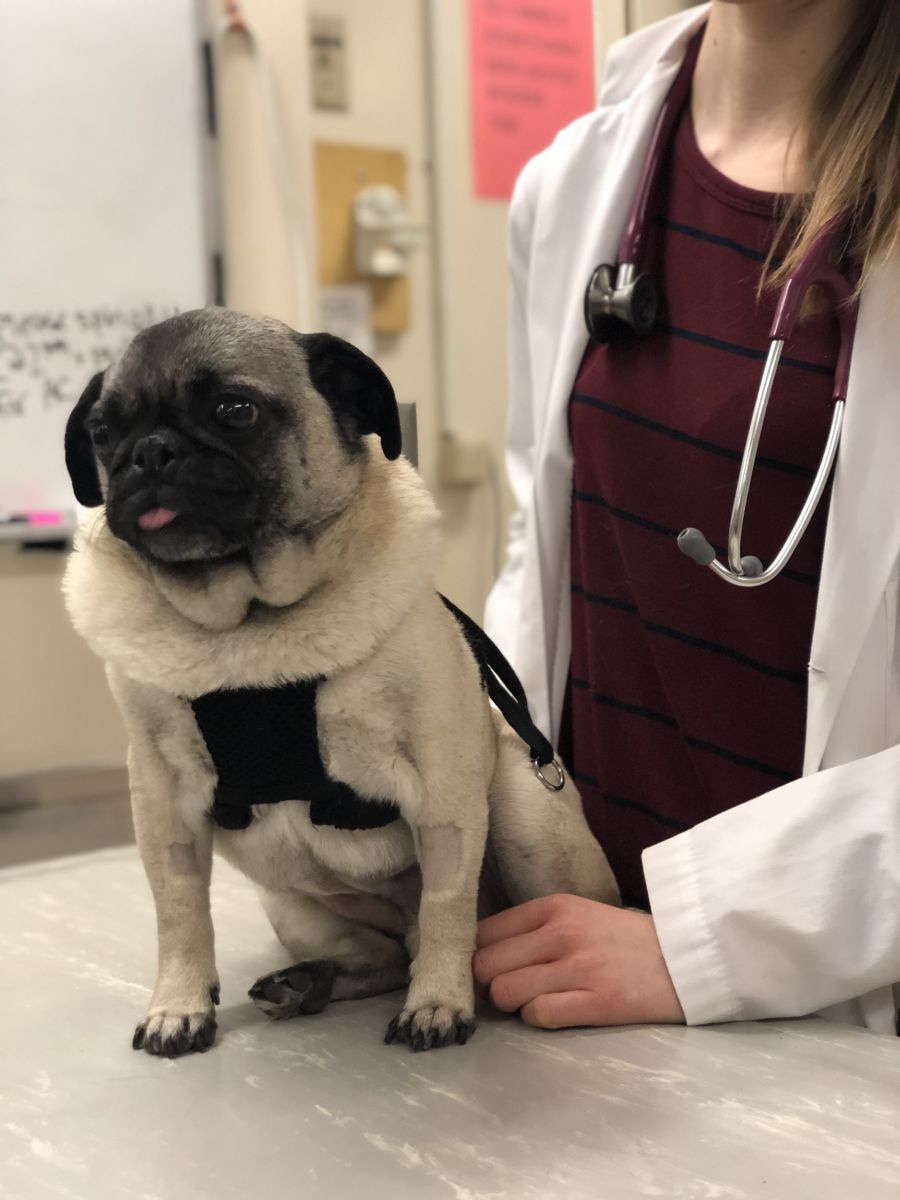

IN PHOTO (left): IBD fecal transplant clinical trial participant, Peanut.

“Research tells us that a wide number of conditions, such as various gastrointestinal (GI) diseases and obesity, are associated with changes in the microbiome,” says Blois. “Right now, there is little known to scientifically determine if these alterations in the microbiome play a role in causing disease or illness or if adjusting cells in the body could serve as a possible treatment option.”

That’s where stool transplants come into play in Blois’ work. Typically referred to as fecal microbiota transplants (FMT) in the medical community, Blois explains the procedure as transplanting feces from a healthy donor into the GI tract of the patient with the goal to replenish “good” bacteria in the body’s system. FMT is commonly known for its use in human medicine, particularly as a treatment for people affected by Clostridium difficile, or C.difficile, infections.

.jpeg)

Blois is currently investigating FMT in veterinary patients specifically as part of the treatment for dogs with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). IBD happens when the immune system attacks the intestines, causing inflammation. It may occur due to multiple factors: genetics, inflammatory triggers in the diet or environment, interactions between the GI tract and normal microbes and changes in the immune system. While IBD includes a broad category of chronic GI inflammation, it is found in dogs, cats, humans and many other species.

IN PHOTOS (left and below): OVC specialist Dr. Shauna Blois and Dr. Allison Collier, DVSc student, with Peanut during a follow-up appointment at the OVC Companion Animal Hospital.

.jpg)

In this study, Blois along with Dr. Scott Weese and OVC Doctor of Veterinary Science (DVSc) student Allison Collier, are measuring the clinical response to FMT in patients that medically qualify as potential candidates and have a pre-existing IBD condition. Pet patient participation is based on owner consent.

“There are a lot of similarities in the way FMT is used in human and veterinary medicine. Donor selection is similar; much like human donors, animal fecal donors are screened extensively to make sure they are healthy and qualify to donate,” Blois explains. Goals are also very similar to human medicine. “The idea behind FMT is that the ‘good’ microbes found in feces from a healthy donor will start to establish themselves in the sick patient’s GI tract and normalize the fecal microbe community again,” she says.

Blois believes OVC is among the first team of researchers to investigate FMT for dogs in a clinical trial for IBD. She is hopeful her work can translate into new treatment options for dog patients. Findings could translate to benefit human health as well.

Depending on the findings, Blois hopes FMT could be the primary treatment for some IBD pet patients, reducing the need for current standard drug therapies which can have severe side effects in patients. If dogs can respond favourably to FMT alone it may eventually help avoid other therapies altogether.

Blois is also currently conducting two related studies that are examining fecal matter. One project investigates the impacts of surgery on the fecal microbiome of dogs and the other explores social impacts, such as housing and environmental conditions, and how they may have an effect on a dog’s fecal microbiome health. Future work is also planned to study microbiome alterations in non-GI diseases such as immune-mediated blood disorders.

“In people and pets, the microbiome includes trillions of bacteria that work together to keep us in optimal health. A healthy gut is the foundation of good health, so the more we can learn about changes in the gut that may cause disease, the better we can treat or prevent those conditions from occurring in the first place,” Blois says.

Read more in the spring / summer issue of Best Friends Magazine.