.jpg)

Veterinary internists are puzzle solvers. They gather the pieces together in many ways in order to form a complete picture of health and disease in their patients, such as: obtaining a patient’s health history from pet owners; interpreting diagnostic images which may include radiography (X-rays), ultrasound, CT or MRI; assessing a patient’s clinical signs; analyzing laboratory results including blood work and biopsy samples; and conducting specialized and complex diagnostic procedures such as endoscopy, a minimally-invasive procedure used to explore and visualize the inside of the body. They methodically fit the puzzle together to arrive at a diagnosis, prognosis and treatment plan for their patient.

(1).jpg)

Much like in human hospitals, Internal Medicine or ‘Medicine’ involves non-surgical techniques to diagnosis and treat acute and chronic disorders or illnesses that involve multiple organ systems. Conditions may include infectious diseases, endocrine disease (for example diabetes), blood diseases (for example anemia), gastrointestinal (GI) diseases, pancreas and liver diseases, kidney and urinary tract diseases and respiratory diseases.

Dr. Allison Collier is an Internal Medicine Resident at the Ontario Veterinary College (OVC). She is currently pursuing a three-year advanced clinical training program to become a board-certified veterinary internal medicine specialist. Her program includes working on the clinical service, treating patients and leading a research project with Dr. Shauna Blois that is investigating fecal transplants as a treatment option for dogs who have been diagnosed with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), a type of GI illness.

MORNING

Allison’s days on the clinic floor involve a variety of collaborative activities. On days like today, she spends her time in appointments consulting with new and returning pet owners and examining her patients; performing endoscopic procedures; and assessing incoming emergencies who are directed to the medicine clinical service. Each morning begins with rounds, an important part of the patient care process, where members of the veterinary medical team review each case and provide updates and discuss next steps in their patients’ progress or treatment plan.

Last year, 223 endoscopies were performed at the OVC Health Sciences Centre; 186 in dogs, 33 in cats and 4 in avian and exotic patients. The internal medicine team works with anesthesiology, diagnostic imaging, registered veterinary technicians (RVTs) and fourth year Doctor of Veterinary Medicine (DVM) students to conduct endoscopy procedures that can take anywhere from one hour, or more, depending on the medical situation.

Today Allison has two patients here for endoscopic procedures. Lulu, a six-year-old Yorkshire Terrier, and Loki, a four-year-old German Shepherd Dog.

.jpg) It is likely Lulu has a protein losing enteropathy, a GI disorder resulting in the loss of body proteins through the intestines. To help connect the puzzle pieces together and to find the answers she is seeking, Allison reviews Lulu’s differential diagnoses, a complex task to distinguish between one particular disease or condition from others that present similar clinical signs. This is an important part of clinical reasoning and decision-making in the health care profession.

It is likely Lulu has a protein losing enteropathy, a GI disorder resulting in the loss of body proteins through the intestines. To help connect the puzzle pieces together and to find the answers she is seeking, Allison reviews Lulu’s differential diagnoses, a complex task to distinguish between one particular disease or condition from others that present similar clinical signs. This is an important part of clinical reasoning and decision-making in the health care profession.

.jpg)

Loki is here today to repeat bloodwork, have an ultrasound examination and proceed with endoscopy. Based on his history and clinical signs, IBD is the most likely diagnosis. Biopsies will hopefully help confirm this diagnosis and rule out other conditions. Allison is hopeful Loki will be able to participate in her fecal transplant study down the road with his owner’s consent, if he is a suitable candidate.

A two-year-old Portuguese Water Dog patient named The Professor arrives. He has been admitted to the hospital with a suspected diagnosis of immune-mediated polyarthritis (IMPA), a condition causing inflammation within the joints, causing pain and difficulty walking. The Professor will be scheduled for a joint tap procedure, in which Allison will use a small needle to remove fluid from various joints in the dog’s body to be microscopically analyzed to help construct a firm diagnosis of IMPA.

AFTERNOON

Between the endoscopy procedures, Allison meticulously keeps track of her various duties throughout the day: pending diagnoses for her patients; monitoring current patients admitted to the hospital; discharging patients; and her ongoing to do-list including paper work and medical chart writing, phone calls and updates to owners and referring veterinarians.

“I love the detective work and the variety of conditions and diseases involved in the specialty of internal medicine, which is why I chose to specialize in this field,” says Allison. “Like many areas of medicine, we rely on diagnostics to get to the bottom of what is making our patient sick to determine the best treatment plan to help them feel better and get them back home with their families.”

.jpg)

Orange, a three-year-old Domestic Shorthair cat, is here for a recheck appointment, and Allison greets her happily. She performs a physical examination on the cat, who has been diagnosed with immune-mediate hemolytic anemia (IMHA), a condition that occurs when the immune system produces antibodies that mistakenly attack its own red blood cells. On top of her diagnosis, Orange has an uncommon blood type. Allison explains the treatment for Orange’s condition involves immunosuppressive therapy; her condition is controlled on an outpatient basis with regular monitoring at OVC.

.jpg)

Allison has a calm, compassionate and hard-working disposition with both her patients and colleagues. She says her lifelong love for animals and seeing how much her family veterinarian made a difference in the lives of her own pets is what inspired her to pursue a career in veterinary medicine. The OVC Companion Animal Hospital is a teaching hospital. She not only learns from and collaborates with OVC faculty and staff clinicians on all specialties, but she is also involved in training fourth year Doctor of Veterinary Medicine (DVM) students who are on their two-week small animal medicine clinical rotation, a part of their veterinary school curriculum.

EVENING

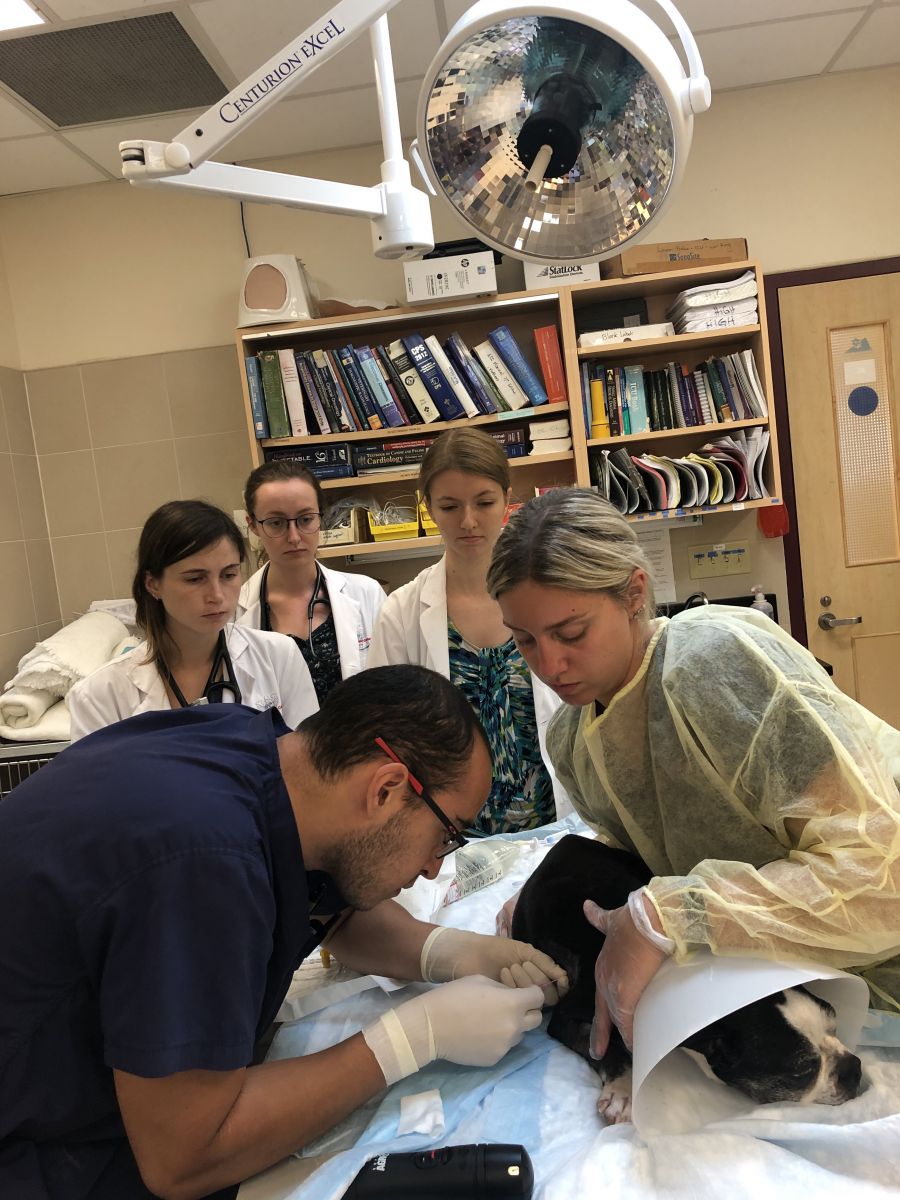

The complexity of diagnosis and number of cases Allison sees in a given day can vary greatly in a tertiary care hospital. The days can be long. As the day ends, Allison checks in on one of her hospitalized patients, Caitlyn, an 11-year-old Boston Terrier, who is in the Intensive Care Unit. Caitlyn had a foreign body removed from her stomach the day before. An ultrasound confirms she has fluid in the pleural space, an area between the lungs and the chest wall.

Allison, along with emergency and critical care residents, performs a thoracentesis, also known as a pleural tap. A needle is carefully inserted to remove excess fluid while Caitlyn is under light anesthesia, which Allison hopes will make Caitlyn more comfortable while she recovers in hospital.

Allison, along with emergency and critical care residents, performs a thoracentesis, also known as a pleural tap. A needle is carefully inserted to remove excess fluid while Caitlyn is under light anesthesia, which Allison hopes will make Caitlyn more comfortable while she recovers in hospital.

End of day rounds are underway, and Dr. Anthony Abrams-Ogg, OVC internal medicine specialist and faculty member, is an encouraging and constructive teacher with residents, interns and DVM students on the medicine rotation. “What is most likely? Have we arrived at our diagnosis? What have we learned today?” He questions each presenter about the cases they’ve worked on today, expertly guiding and proposing next steps in their care.

Veterinary specialty training can be rigorous. Allison’s days on clinics are usually 12 to 13 hours, unless she is on call, and then she must also be available to receive incoming emergency patients that present to OVC overnight.

.jpg)

“My residency is very rewarding. I love forming bonds with our patients and families as we care for their pets in hospital and over time through recheck examinations,” Allison says. “Although the hours may be long, I am so fortunate to be able to work with and learn from such a wonderful and caring team of fellow residents, interns, faculty, technicians and students to offer the very best health care for our patients. Like many of my colleagues, I became a veterinarian because I had a deep desire to help animals. It is very satisfying to help patients, many with complex health conditions, feel better and send them home to their families where they belong.”

Read more in the fall / winter issue of Best Friends Magazine.