OVC Pet Trust-funded research guides veterinarians on most effective stabilization techniques in canine spinal surgery

Monkey at OVC Companion Animal Hospital five weeks post-op. Follow Monkey’s journey on his Instagram account @MonkeyStern.

The Neurology team at the University of Guelph’s Ontario Veterinary College (OVC) would describe Monkey with one word: survivor.

And that’s just what Monkey has been doing since his spinal cord injury diagnosis in 2012. The seven-year-old Yorkshire Terrier had been medically managed for atlantoaxial (AA) luxation, a type of congenital malformation causing spinal cord injury common in small dog breeds, for the past three years of his life. AA luxation occurs when there is instability between the first and second cervical vertebrae.

Upon diagnosis, Monkey was kept under supervision at OVC for two weeks. When he was able to go home, he was in a full body cast for two months. With time and ongoing visits to OVC, Monkey eventually had his cast removed, and resumed his active lifestyle. Monkey had been doing well until his condition began to drastically deteriorate in September 2015, and surgical intervention became the only option to restore Monkey’s health. The major concern for dog owners with a pet with this condition is that sudden death can occur unexpectedly with excessive motion of the neck, or even during an attempt at surgical repair.

|

|

Mend and Arieanne Stern hold Monkey in their arms at a December 2015 follow-up appointment at the OVC Companion Animal Hospital waiting room. Mend describes Monkey as an independent dog resembling a teddy bear, who enjoys lots of love and attention. The cuddly Yorkie, wearing a grey cable-knit sweater, is able to walk across the couch in the waiting room with little difficulty, a significant improvement from only a couple short months ago.

|

Mend and Arieanne adopted Monkey from a friend who could no longer care for him in 2011. He’s been a special part of their family for the past four years. Arieanne says that the team at the OVC have consistently cared for Monkey as if he were their own, and her family feels gratitude, comfort and relief knowing that they saved his life.

|

Senior neurology resident and Doctor of Veterinary Science (DVSc) student Guillaume Leblond has been involved in Monkey’s care since the Yorkie’s first visit to OVC in 2012, and played a major role in the life-saving procedure Monkey underwent. The DVSc program is a unique post-professional degree, involving advanced clinical training, research and coursework at a doctoral level at OVC.

Surgical repair of AA luxation is one of the most challenging procedures performed by veterinary neurosurgeons, says Dr. Fiona James, Assistant Professor in Neurology and Neurosurgery in the Department of Clinical Studies at OVC. “AA luxation is a common condition in miniature dog breeds like Monkey,” James says. “Leblond’s graduate research at OVC played a direct role in targeting the most effective spacing and positioning of the surgical implants we used to stabilize Monkey’s vertebrae.”

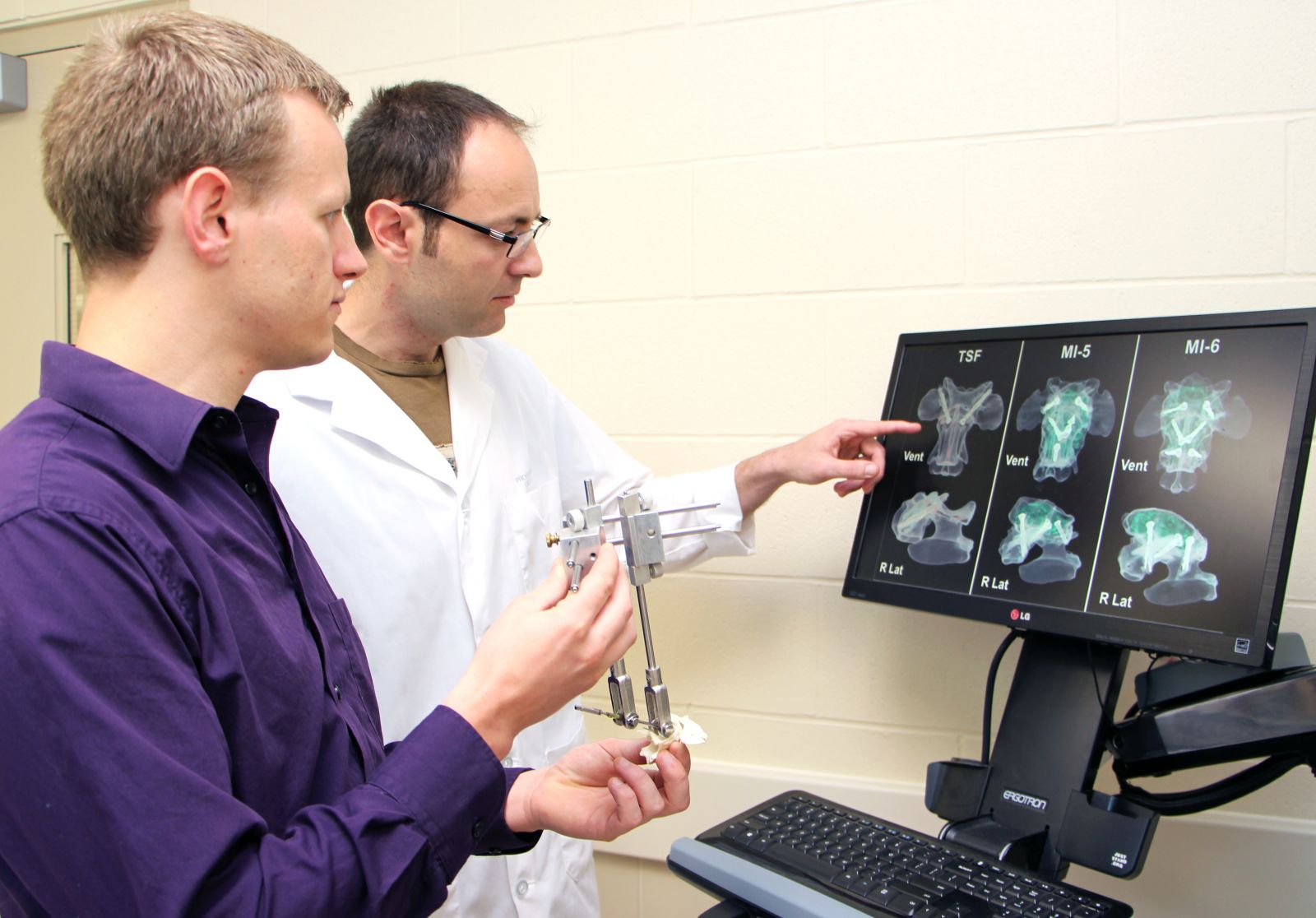

The ability to demonstrate immediate clinical applications of his research was important to Leblond, as translating academic results to patients is an important part of studying at a teaching hospital like OVC. OVC Neurology’s Dr. Luis Gaitero, who was Leblond’s primary supervisor and principal investigator of the research project, worked closely with him throughout his residency. Since commonly-affected dogs are very small, implants can be difficult to position. “My research defined as precisely as possible how to most effectively place surgical implants. We also proposed a new method of surgical planning using modern CT scan imaging and software techniques,” Leblond explains.

Drs. Leblond and Gaitero used CT imaging to determine safe corridors for implants during spinal cord surgery in miniature dog breeds

Drs. Leblond and James performed surgical stabilization on Monkey this past September. With approximately 80 per cent chance of success, the procedure required delicate precision, since Monkey’s spinal cord was already damaged. Initially, Leblond placed two screws within the first two vertebrae. Three more implants were added after evaluating the placement of the first two screws with a CT scan, an important component of Leblond’s research. All implants were then cemented together, forming an internal “cast”. The procedure is a balancing act: the three additional screws strengthened the connection, but there is also the potential for risks associated with the placement of more implants. Luckily, the procedure was successful for Monkey.

Leblond’s DVSc position and research project are both funded by OVC Pet Trust, and he is grateful for the support. “I owe my training and successes to the generous donors who support OVC Pet Trust – they are a major funding resource to many researchers at OVC, and in my case, the support allowed me to advance my project beyond what I initially anticipated.”

As for Monkey, Mend and Arieanne plan to continue with physical rehabilitation with the hope that he will eventually fully recover. Rehabilitation following neurosurgery helps patients maintain muscle mass and mobility while learning to walk again.

“The Neurology service put our family member back together again. We want to thank everyone at OVC for caring for Monkey, including his doctors and all of the students who helped care for him. They gave us our dog back.”

Dr. Fiona James and Dr. Randy Cochran look at Monkey’s imaging during a post-operative appointment in December 2015

To learn more about Leblond’s research, read the following article via OVC: Mathematical precision key to implant success.

Get Social! Connect with OVC Pet Trust on Facebook and Twitter @OVCPetTrust