OVC trials new technology to illuminate and destroy tumours

An innovative “seek and destroy” alternative to cancer surgery for people and pets is being tested for the first time at the University of Guelph’s Ontario Veterinary College (OVC). Combining nanotechnology and laser light therapy, the new technique may ultimately offer a targeted, non-surgical way to diagnose and treat tumours, while preventing over-treatment and reducing common side effects. The promising new treatment has potential to change the way we treat and diagnose cancer in the future, says surgical oncologist Dr. Michelle Oblak.

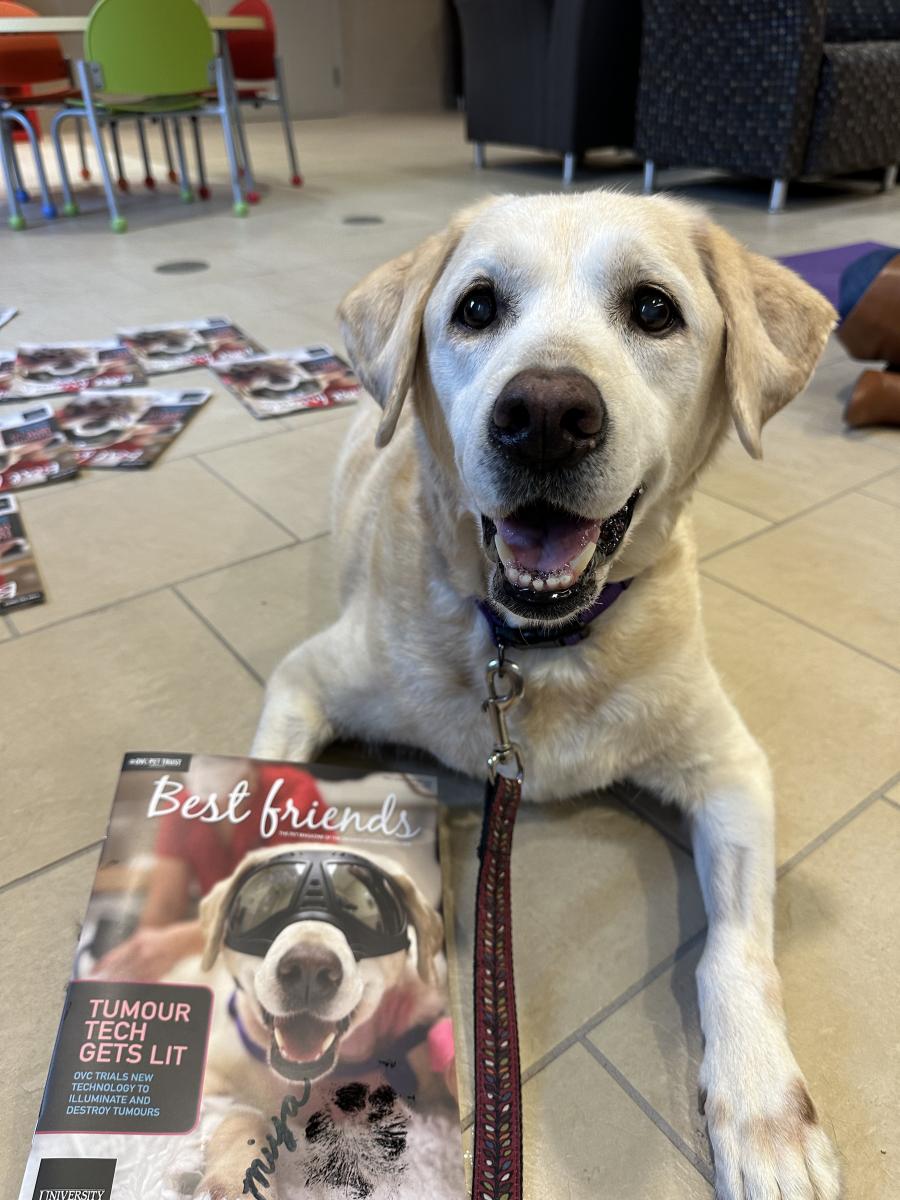

Weeks before her dog Miya’s cancer diagnosis, Liz Pietrzak noticed some changes in the 10-year-old Labrador retriever’s behaviour. Miya seemed to be panting more and seeking out cooler, drafty areas to rest. And the usually “chunky” dog, who Pietrzak describes as “one of those butterball labs,” had lost some weight.

Miya’s veterinarian ran some tests and called Liz to give her the news. “She said, ‘we found something, and we think it’s cancer,’” Liz recalls. “Miya never had anything wrong with her until then.”

Miya was diagnosed with thyroid cancer and referred to the Ontario Veterinary College (OVC) for treatment. OVC’s standard of care for thyroid tumours involves surgery to remove the tumour, but Pietrzak was notified of an additional opportunity: an OVC research team was seeking ten dogs to participate in a clinical trial to evaluate a new medical treatment for cancerous tumours in companion animals.

The inventors of the technology, partners at the University Health Network (UHN), plan to evaluate this same technology in humans, which may lead to a parallel trial on human thyroid cancer patients. Pietrzak agreed that Miya would be dog number two in the trial.

PROMISING NEW TREATMENT TESTING UNDERWAY

The trial is being led at OVC by Dr. Michelle Oblak, surgical oncologist and Animal Health Partners Research Chair in Veterinary Medical Innovation, and it combines the use of two medical technologies. Together, the treatments offer a promising “seek and destroy” approach to cancer treatment for companion animals as well as humans.

The trial is being led at OVC by Dr. Michelle Oblak, surgical oncologist and Animal Health Partners Research Chair in Veterinary Medical Innovation, and it combines the use of two medical technologies. Together, the treatments offer a promising “seek and destroy” approach to cancer treatment for companion animals as well as humans.

First, a medical team injects tiny particles called porphysomes through an intravenous (IV); the porphysomes circulate through the body and accumulate in tumours. Then, the team uses a specialized camera and near-infrared fluorescence (NIRF) light to make the cancerous cells “glow in the dark” so they are easier to see. Finally, the team uses photodynamic therapy (PDT)—a type of laser—to create a path of destruction within the tumour.

“Porphysomes are multipurpose, because they help with im-age-guided surgery and margin assessment, and they also make tumour cells more penetrable to laser light, or PDT,” says Oblak (pictured in the operating room). “We see this treatment having applications for less invasive treatment approaches in the near future.”

THE PROBLEM WITH CANCER RESEARCH

Although researchers have been working with porphysomes for a decade, this is the first time they are being used on patients with naturally occurring cancer. An estimated 94 per cent of cancer therapies developed using mice models fail to produce effective therapies in humans, but Oblak sees potential in using companion animals as models for human diseases and treatments.

It’s a branch of research known as ‘translational medicine’ because humans and companion animals have so much in common.

“Our pets have huge genetic diversity, and they live in a shared, complex environment with humans,” says Oblak. “When they develop naturally-occurring diseases, it presents an almost perfect model for the development of new treatments.”

WHY CLINICAL TRIALS?

Charly McKenna, research manager of the Veterinary Innovation Platform at OVC, says participants in clinical trials are vital to advancing knowledge and techniques in companion animal medicine. While each clinical trial may look a little different, the approach is always the same: patients have access to the highest standard of care using proven treatments, in addition to new and emerging technologies and therapies. This ensures patient out-comes are not compromised as these new treatments are being developed and perfected.

“We want to understand at what point the maximum amount of porphysomes get into the tumour and when the ideal timing of the PDT procedure might be, but we aren’t ready to use this as a treatment just yet,” says Oblak.

McKenna says this study is an example of one that will not necessarily provide any additional benefit for the current participants, but it will benefit dogs, cats and humans in the future.

“Our study participants are still having their whole thyroid tumour removed, and receiving the full standard of care,” says McKenna. “This is how we learn and further our knowledge, through patient trials, and pet owners who want to participate. We are thankful for families—like Miya’s—that enroll in our studies.”

“Our study participants are still having their whole thyroid tumour removed, and receiving the full standard of care,” says McKenna. “This is how we learn and further our knowledge, through patient trials, and pet owners who want to participate. We are thankful for families—like Miya’s—that enroll in our studies.”

For Pietrzak, the experience of participating in the clinical trial was a positive one. She feels good about the care Miya—and the whole family—received at OVC.

“The entire medical team took time with us, they answered all of our questions, and sent us messages and pictures to show us how well she was doing,” says Pietrzak.

Miya’s cancer has not progressed to her lymph nodes, and she has made a full recovery.

“Miya is a retired Red Cross therapy dog, and she has always been giving back to somebody, so we thought, ‘why not?’” Pietrzak says. “First, it helped Miya. Second, it will help us all. It furthers our understanding of cancer in dogs, cats and humans. I think that’s amazing.”

“Miya is a retired Red Cross therapy dog, and she has always been giving back to somebody, so we thought, ‘why not?’” Pietrzak says. “First, it helped Miya. Second, it will help us all. It furthers our understanding of cancer in dogs, cats and humans. I think that’s amazing.”

For more information, visit the OVC Clinical Trials website.

This story originally appeared in the fall 2022 / winter 2023 issue of OVC Pet Trust's Best Friends Magazine. Join our community and subscribe to the pet magazine of the Ontario Veterinary College.

Learn more about the work of OVC Pet Trust.